Description

Please join 221A Fellows, Architects for Social Housing (ASH), for a workshop on the economic implications and social development strategies that are born from the global housing crisis. This workshop is the third in a series of four, which take place Friday afternoons from July 19 to August 9, 2019. The third workshop ‘The Economic” workshop is co-convened with Ross Gentleman, former CEO of CCEC Credit Union and the Treasurer on 221A’s Board of Directors. The Economic workshop asks the questions:

- What are the ideal economic conditions for a socialist architecture?

- What are the actual economic conditions for a socialist architecture?

- What is a socialist architecture under capitalism?

- What funding revenues are there for a socialist architecture?

- How can architecture be socialist under capitalism?

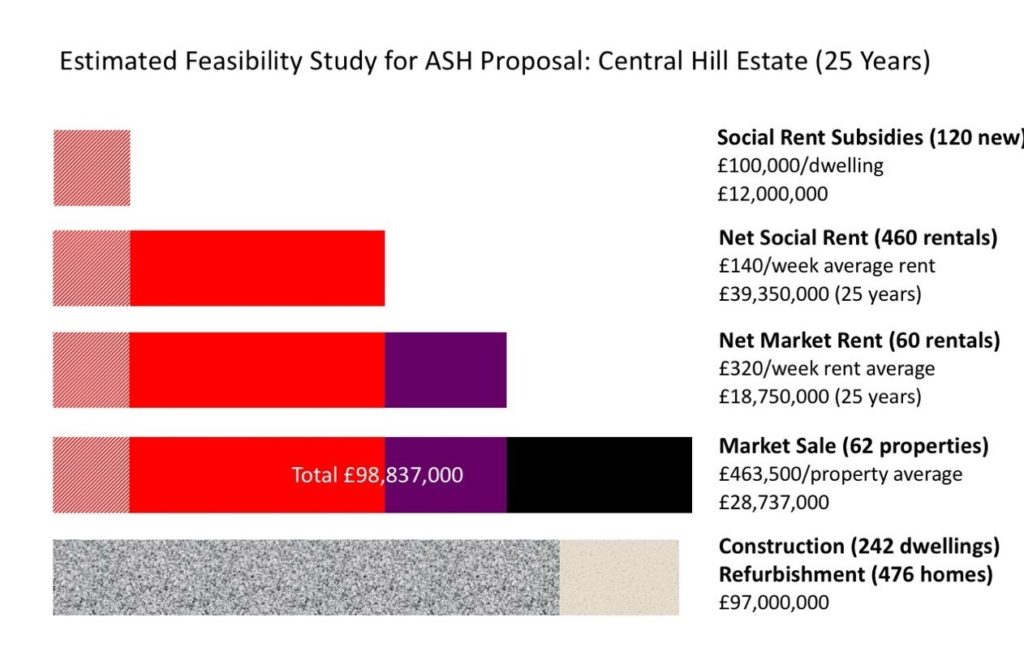

The obvious way to fund the homes for social rent or equivalent that constitutes the greatest housing need for a growing homeless population is for governments to invest in it sufficiently, as they should any essential infrastructure, thereby removing the responsibility for new-build housing provision from the market altogether. In the absence of such funding, however, or anything like it, ASH has found itself asking whether a socialist architecture can exist within a capitalist system; and, if it can, what would it look like? The key to answering this question lies in the way in which projects are financed.

The architectural profession’s current culture of demolition and redevelopment – of the erasure of the historical layers of the city and the construction of the always new commodity – is driven not by concern for the most sustainable solution to a brief, but by the desire to make and maintain a name for an architectural practice with a recognisable brand or – when that brand has already been established – to meet the developer’s desire for a signature building. The skylines of the world’s wealthiest cities, surrounded by neglected and run-down slums and favelas, is ample testament to the social consequences of this culture. At the base of this culture, however, is the commercial inducement of calculating architects’ fees as a percentage of the total cost of the project, rather than its total social value.

A socialist architecture, by contrast, subordinates such marketing concerns to the use and function of the building in meeting the total requirements of the scheme; and the decision not to demolish, but to refurbish, to improve, and where possible to add, must be the default point of departure. The answer, already formulated by Lacaton and Vassal Architects in France, is simple. Do not demolish structurally-sound dwellings in which people have made their homes and communities, but refurbish them and – where possible and with the consent of the residents – increase housing capacity with infill and roof extensions.

A socialist architect must produce an impact assessment of the financial costs to both the local authority and residents, both existing and future; the social costs for existing residents of the estate as well as those who live in the neighbourhood and will be affected by any new development; and the environmental costs, not only of the embodied carbon lost, but the carbon emissions from demolition and construction, and the environmental impact of the use of additional buildings, in terms of both energy use and carbon emissions from, for instance, increased car use, as well as the impact on local services, such as roads, schools, clinics, hospitals, police and fire services.

Such impact assessments are different from a financial viability assessment calculating the gross development value of a scheme; or calculating, for example, the additional income to the chain stores and supermarkets that will benefit from the gentrification of a neighbourhood consequent upon building high-value property in the area; or again the rise in house and land values for property- and land-owners who will benefit according to the land value uplift in an area consequent upon development of a scheme.

The so-called ‘law’ of supply and demand, as an economic model for the marketization of housing provision, is not a mechanism for reducing house prices but an excuse for increasing the profits of developers and investors. In contrast, a socialist architecture must look at the use-value of its productions, and not merely at their exchange-value as commodities.

The financial roots of this crisis reach deep into the world economy, and architects must do more than bury their heads in the limitations of a developer’s brief, confine themselves to purely formal interpretations of housing typologies imposed by developers to maximize land values, attend award ceremonies to their own complicity in the failed and failing marketization of housing provision, and become just another cog in the building industry.

ASH has worked for nearly five-years from London to develop a robust and detailed critique of the United Kingdom’s housing policy. By working alongside housing campaigners, they have studied the disastrous impact this crisis is having on housing, poverty, and homelessness. ASH has also developed practical designs and policy interventions in housing provision that demonstrate there is another way.