Description

Please join 221A Fellows, Architects for Social Housing (ASH), for a workshop on the environmental implications and social development strategies that are born from the global housing crisis. This workshop is the second in a series of four, which take place Friday afternoons from July 19 to August 9, 2019. The second workshop, “The Environmental”, is co-developed and hosted with Daniel Roehr, Landscape Architect and Professor at the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, to ask the questions:

- What is the environmental context of architecture?

- What is the environment for a socialist architecture?

- What is the difference between the environment and sustainability?

- How is socialist architecture sustainable?

- What does socialist architecture sustain?

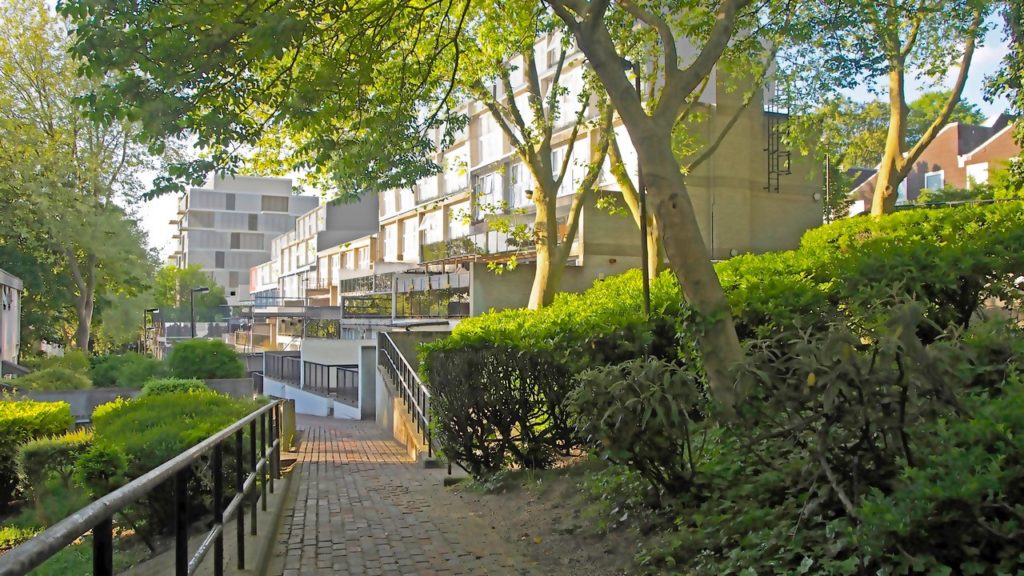

In addition to the huge financial costs and debt risk associated with the demolition of existing social housing and its privatized redevelopment as properties for market sale, the environmental costs of both are huge, ranging from the loss of the embodied carbon in the existing buildings to the pollution in the air from demolition and disposal, to the carbon cost and environmental impact of the new buildings.

Green roofs and walls, solar paneling, improved thermal performance and the reduced energy consumption of modern buildings are not enough to offset this environmental impact. The environmental sustainability of housing needs to be taken as a totality. It has been estimated that it will take at least 30 years for the more environmentally efficient buildings one might expect to be built on new developments to recoup the environmental losses of demolition and redevelopment.

A commitment to reducing carbon emissions and to policies of economic de-growth is inevitably a socialist concern, not least because damage to the environment has enormous collective social and economic consequences. While maintaining that only a socialist economy can hope to re-order the relations of production to sustainable levels of consumption, a socialist architecture must seek to ameliorate, resist and challenge the unsustainable growth on which capitalism depends for its profits.

Under capitalism, the global consequences of expansion are not estimated in individual project costs but deferred, manifesting themselves in the health or social well-being of future generations, or in contributions to the long-term destruction of our global environment. A socialist architecture, by contrast, must calculate and mitigate the social and environmental costs of any given project.

The financial roots of this crisis reach deep into the world economy, and architects must do more than bury their heads in the limitations of a developer’s brief, confine themselves to purely formal interpretations of housing typologies imposed by developers to maximize land values, attend award ceremonies to their own complicity in the failed and failing marketization of housing provision, and become just another cog in the building industry.

ASH has worked for nearly five-years from London to develop a robust and detailed critique of the United Kingdom’s housing policy. By working alongside housing campaigners, they have studied the disastrous impact this crisis is having on housing, poverty, and homelessness. ASH has also developed practical designs and policy interventions in housing provision that demonstrate there is another way.